ZELDA BOMBA

I would like art to be as much a part of everyday life as a news program or a café in a bar, something democratic, accessible to everyone, close at hand.

What’s behind the name Zelda Bomba?

Without ever giving it much thought, having a pseudonym always seemed obvious to me. I would never have entered the world of art under my real name, I think, a bit out of shyness; when I was younger, I wanted to hide somewhat.

Zelda is a name that seemed strong to me; it is not related to the game, which I didn’t even know and which is not part of my culture. I added Bomba when the internet arrived, when I had to create an e-mail address. Bomba because it was the explosive period after September 11th: it came to me like that, it was the air you breathed. In the end, it all happened a bit by chance, without giving it too much importance, but this name still matches me…

When and why did you start making (public) art? What are your sources of inspiration?

Public art has always attracted me a lot. The first book I bought with my money was Spray Can Art. It fascinated me. I also had a lot of writer friends that I used to take to Rome when they went to paint, but I used to watch. Let’s say I never picked up the cans – I paint with a brush, which is a much longer thing – so I waited for the possibility of having legal walls to make large-scale works in the street. Maybe in 2012?

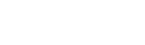

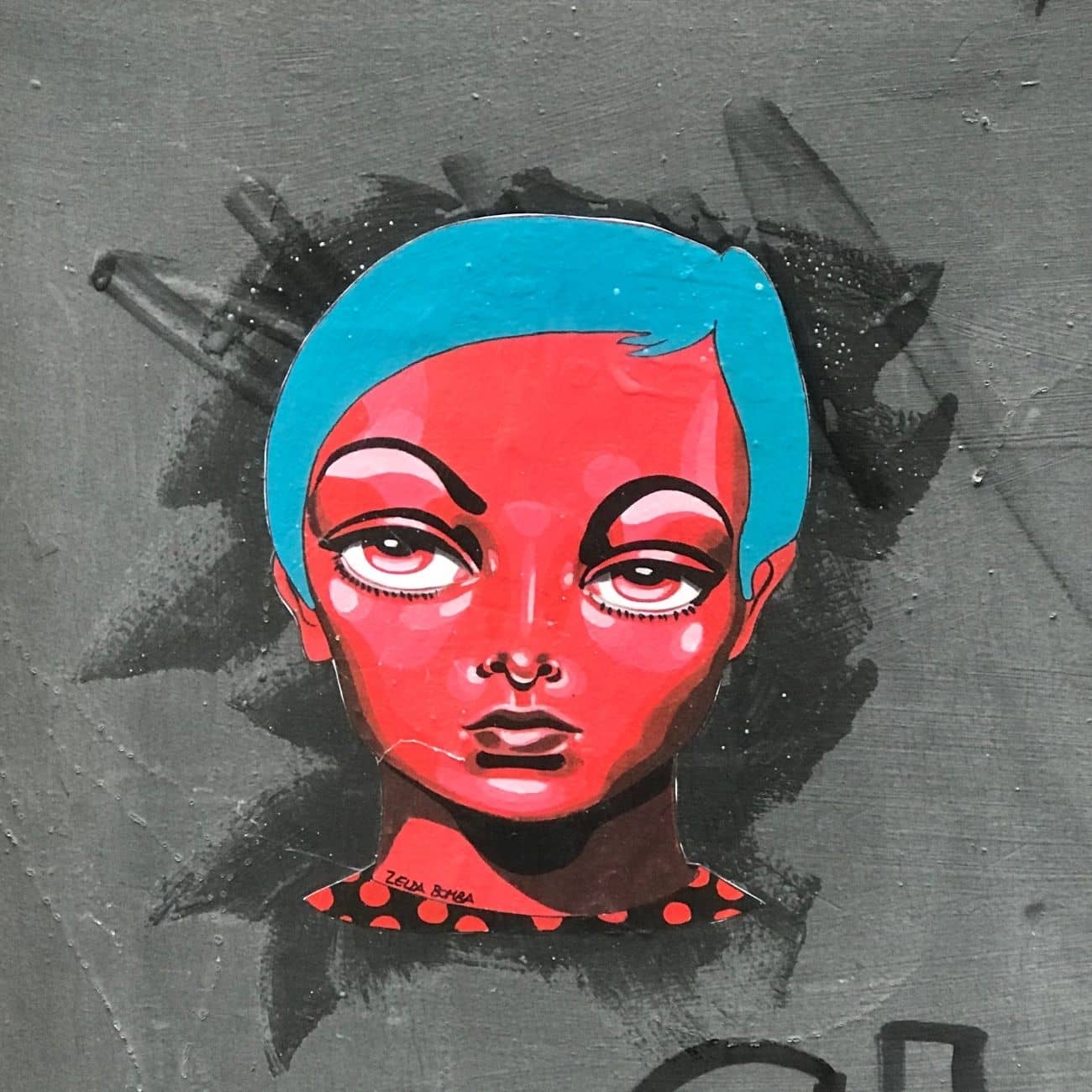

I then developed my public art in the form of collages, which fit me more because I can develop them as much as I want in my studio and then go around pasting them wherever I want.

For me, it is a way of meeting people surrounding art in a different way. When I work in Belleville in Paris, I know that the people who will see my work are a very diverse multitude and very different from the people you meet in the gallery. So, not only is it a way to communicate art in a more democratic way, but it also forces me to adapt my work to address different people: children, maybe people who are not used to going to museums. It is a way to create a bubble of color and I hope that those who meet a collage of mine on their way through the city will like it. Obviously, it is also a way to take over the city polluted by advertising.

How would you define “urban art”?

For me, it is a way to make free art exist, for everyone, in cities consumed by private individuals. Anyone can do it, and all messages can be expressed on the street.

For artists, it is a way of investing in the city that becomes a terrain of adventure (I discovered areas of Paris looking for new areas of expression that I didn’t know at all) and also of inspiration.

Art can therefore be part of people’s everyday life: in a simple way, anyone can take possession of it and include it in their vision of the city. It can create emulation.

When I was a child, I was very impressed by the stencils I saw around the city. They were few at the time, but they intrigued me. They truly seemed inspiring to me, almost mysterious how they appeared in the night, with no noise.

Rethinking the city with art and nature seems to me a necessary thing, more and more…

Are urban art, galleries and traditional art institutions mutually contradictory, or is a wider recognition of the street art movement by the traditional art industry long overdue?

I have to say that I have moved away from these reflections even though they are obviously part of street art. I don’t really understand how the dialogue between galleries and street art can be harmoniously articulated. I guess it also depends on the actors on the ground. Everything that has an opportunistic matrix is not high quality in my opinion. Personally, I have moved away from certain realities of this kind, continuing my work on the street without tying myself to institutions or galleries.

But it is also true that there are projects, even those linked to galleries, that are ambitious and high quality, as is the case in the 13th arrondissement of Paris with Tour 13, a building occupied by many quality artists, which became an ephemeral museum before its destruction, or the facades of the buildings along the route of line 6 of the aerial subway, which offer an open-air museum to travelers.

I also took part in the Bristol Upfest, which is a real folk festival. Practically the whole city takes part in it. I really like it; it’s a real moment of sharing.

Are there any differences between the works and the messages you put on the street and, for example, your illustrations and works on paper?

Yes, they are two different things and that’s what interests me. The painting work that I have been doing for years, in my studio, is very self-referential, very obsessive; it is a personal research that I have been doing for years.

On the street, I try to use other references, to talk to people more than to myself, to communicate. I also use a red and blue color code (which is that of road signs). On the street, I try to represent the street – men, women, from all parts of the world as you can see in Paris – and then sometimes I bring in icons of popular culture like Bruce Lee, Spike Lee, Malcolm X, Kim Jong-un, Twiggy, and many others. This can be a tribute or even something to make people smile.

Can you describe your process of working? How much time do you spend on a work?

It depends… I use various ways to work on the street: a more Warholian method is to create a visual (on food packaging) and then reproduce it as much as you want to glue it. This may take me five hours. If I make a big painting on parcel paper, always for paste-ups, maybe I work two days on it (I’m fast but I don’t do anything else, so it’s still hours of work).

For my paintings not intended for the street, it’s the same: two or three days.

My work process is in the studio, alone, with selected podcasts and total immersion until I’m finished. I work with acrylic, on paper, and recently also on wood.

It is one’s own need to paint, which does not disappear with time; indeed, it grows. For me, it is research, and always the search for evolution…

You have an extraordinary style, which is rooted in counterculture, comics, music, fashion and street life, with a strong recognition value and a lively color palette. How did you develop your unique style, and what message do you want to convey with your art?

Development is simple: work. I made the decision to do practically nothing else and, therefore, the style develops naturally. Obviously, you have to feed it, and this happens through readings, meetings, other artists, films, culture in general; these very often inspire you unconsciously. The desire to do and to find new creative solutions is, however, for me, the most powerful trigger.

The message… I don’t have a message because I have discovered that if a person wants to see a message in what you do, that message belongs more to them than to you. Or it is an alchemy, let’s say, between what you produce and how it is perceived by that particular person. No two people perceive a work in the same way.

But maybe if I had a message it would be to encourage people to use their creativity, in whatever way, to keep alive this part that absolutely everyone has. It often happens to me, when I do workshops with people who are completely unrelated to creativity, to hear “I’m not good at anything,” and then see at the end of the workshop that everyone has managed to create, even in an unexpected, rich way, which is an extremely valuable thing, which everyone needs. I am absolutely for the development of these possibilities, which are buried in everyone. They do well; they create a different way of seeing life, of seeing oneself. They make people happy. It is very important.

What relationship do you want to create with the viewers of your works?

Maybe emulation. I would like art to be as much a part of everyday life as a news program or a café in a bar, something democratic, accessible to everyone, close at hand. We can all be artists; we can all be artists even if it’s for only ten minutes a day… This is what street art can be: meeting a drawing in the street on the way to work, which was made there for you, distracting you from your thoughts for a moment… You have to break the distance between people and your creativity.

Is there a reason why you mainly paint female figures?

Female figures are mainly present in my painting not intended for the street. Yes, obviously, since I question the concept of identity a lot, I start from one of my personal identities, which is female.

The social construction of femininity then offers endless creative possibilities in its representation, which also borders on the queer.

On the street, unconsciously, I create more men. I have wondered about this fact without finding answers, besides the fact that it is an objective mirror of reality.

_______________________________________

Zelda Bomba

Tours / Paris, France

_______________________________________

November 2020 I Laura Vetter